21 February 2013

Book review: Caucasus by Nicholas Griffin

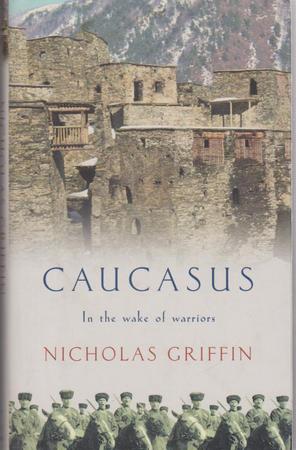

Caucasus — In the wake of warriors

Caucasus — In the wake of warriors

Nicholas Griffin

Review, London

August 2001

256 pages

ISBN: 978-0-7472-3630-6

(In subsequent years republished with a variety of different subtitles (A Journey, A Journey in the Crucible of Civilisation, A Journey to the Land between Christianity and Islam and Mountain Men and Holy Wars) and different covers (and various combinations of the two) by Review and other publishers (Thomas Dunne Books (and St. Martin's Press, of which it is an imprint), University of Chicago Press). At one point I thought Nicholas Griffin might have written a whole series of books set in the Caucasus.)

Despite its apparent popularity in the West (as evidenced by its publishing history), I hadn't heard too much good about Caucasus, yet was willing to be positively surprised. The book is primarily about Imam Shamil, but the chapters tracing his rise and fall are interweaved with the account of a trip the author made to the Caucasus in 1999.

As feared, Caucasus does contain a significant number of gaffes. When stating that in Yerevan "the European influence is obvious", the first piece of evidence produced to support this is the observation that "everywhere there are people sipping coffee". Other dubious assertions include that "what brings the lands of the Caucasus above simpler questions like nationalism and self-determination is oil", that Stalin is the Caucasus's most famous hero, that it was "only because of Shamil" that the Caucasus hadn't yet been fully conquered in the 1870s (completely ignoring the war in the Northwest Caucasus), that the Parthians that defeated Marcus Licinius Crassus at the Battle of Carrhae were 'nomads', that "in 1990 [...] Armenia invaded the region of Karabagh" and that Zakatala in Azerbaijan is the unofficial capital of Avaria.

Perhaps the most cringe-inducing moments however come when Griffin talks about language, characterising Armenian as "the oldest alphabet in the world, entirely phonetic". And puzzled by the Caucasus's linguistic diversity, he states that "There are such diverse explanations for the languages of the Caucasus that no single one makes sense", "In neighbouring villages professors have found Turkic, Indo-European and Caucasian tongues. Quite how this happened no one knows." and "Germans colonized a small portion of central Georgia. Christianity took root in Ossetian lands, bringing with it scraps of Latin."

Caucasus should not be disqualified solely on the basis of these examples. Unfortunately, the rest of the book also disappoints. The account of Shamil's life is at times exciting, but by its nature cannot be more than introductory. The writing suffers from overinterpretation and clichéd language, and Griffin at times verges dangerously close to making Shamil look like a saint, although he at least acknowledges that Shamil too committed atrocities, and does not fail to point out the fact that throughout the Murid wars, civilians were caught between a rock and a hard place. More worryingly — especially in the light of the mistakes illustrated above — there is no way for the reader to assess the extent to which the text is historically accurate. This because the account seems to be partially fictionalised (Griffin had written two novels before Caucasus), but the extent is not stated, and because references are provided extremely sparingly.

All this could still be compensated for if Griffin's road trip provided any insights into Shamil's legacy in present day society, or the state of the Caucasus in 1999. Alas, Griffin's expedition, starting off in Baku, doesn't make it to Chechnya (understandably), and Dagestan is only reached by one team member, who is sent across the border for two days. The closest Griffin gets to Shamil is when they visit the Georgian estate of Tsinondali, which Shamil famously raided (capturing Princess Varvara Orbeliani, her niece and her French governess, whom he was then able to trade for his son, raised at the Russian court), and when talking to Shamil's great-great-granddaughter Tamara (whose family story is perhaps the single most interesting element of the book). The general geographic disconnect between Griffin's journey and Imam Shamil's legacy reaches a low point when in Armenia the author seems perplexed that Shamil does not occupy a prominent place in the national consciousness.

We also don't learn too much about the people the travel party interacts with, apart from their general hospitality and its occasional limits. This is mostly because the varying tensions and companionship within the group require too great a share of the author's attention. Griffin successfully convinces the reader that the expedition itself was deeply memorable for its participants, but the ultimate levity of the various incidents makes their description unmemorable for the reader.

Caucasus may still be enjoyable for individual readers for whom the Caucasus is a new topic, but there is a risk they carry away from it a shallow impression, and the generally high quality of Caucasus literature means there are better alternatives available.